and people had names for all the shades of grey,

value defined everything.

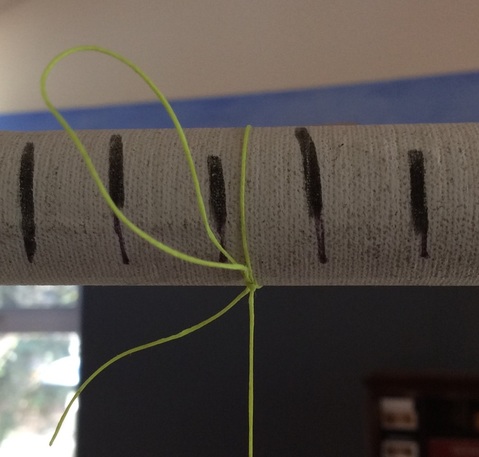

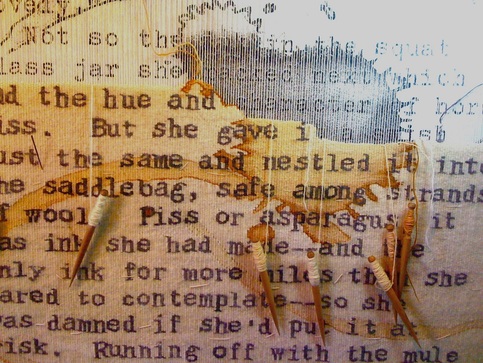

planted cups on tables, scribed undulations into cloth

and gave definition to faces.

It still does.

so a stick of butter looks like a stick of butter and an egg appears smoothly curved because the surfaces of objects are defined by light and shadow rather than by words.

A box of baking soda, which we might notice first because of its distinctive orange hue, is recognizable in black and white because of its proportions and the awkwardly torn opening at the top. A weaver rendering such a box is helped as much by the value-- the relative lightness and darkness of the parts of the box -- as by the color.

Further, when placing that box of baking soda in a composition without the distraction of color, it is useful to see that the dark side of the baking soda box is darker than the dark side of the butter and that the richest part of the shadow cast by the butter is darker than both. This is important information whether the objects are the hue we expect, or not.

Every region had its own particular hue: one place was blue, another golden.

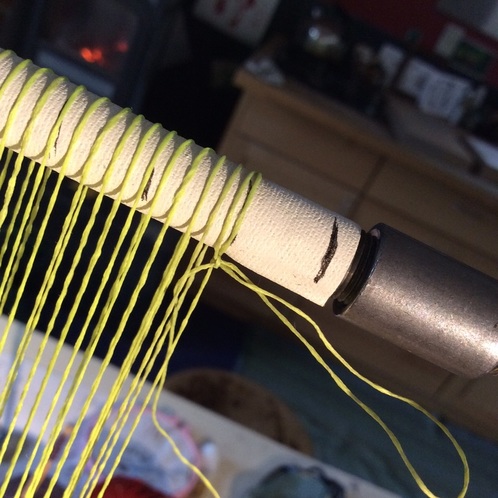

Regional sheep colors would have ranged from dark to light in the hue of that area,

as would yarn: alabaster to ebony here, blush to burgundy there,

and no matter the underlying color

the range of value, from light to dark and back again

would be pretty much the same.

--this is the darkest and this will be the lightest --

select yarn to match their idea, and begin.

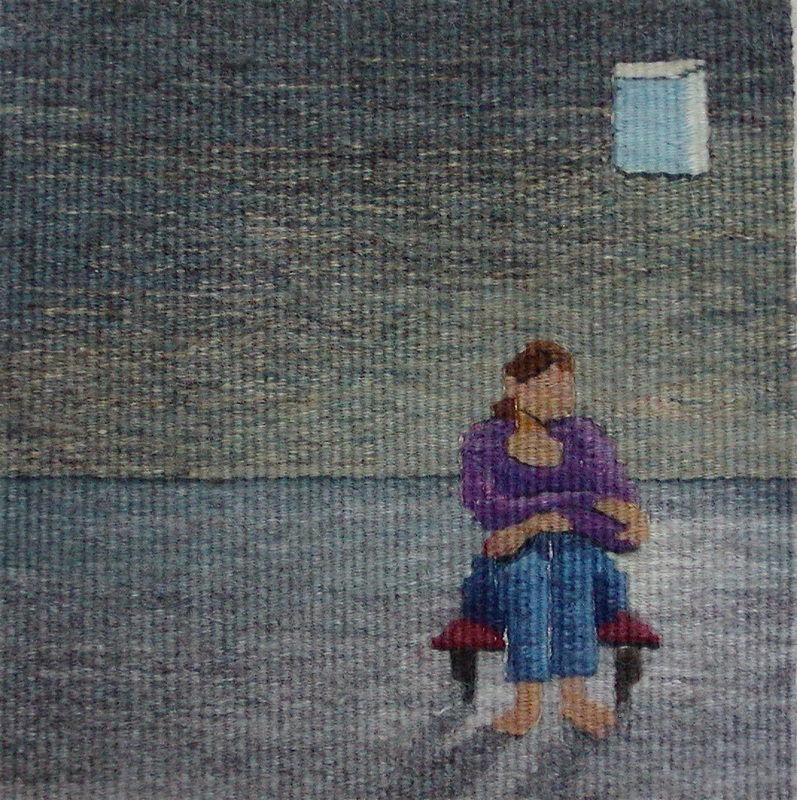

and I sometimes weave as though I am still there.

Eliminating color clarifies my thinking, defines an unfolding composition,

and allows me to focus on mood.

I can ask (and hopefully answer), one specific question at at time.

Value Question: How light will my lightest area be on this drawing, how dark the darkest,

and how many steps do I want between?

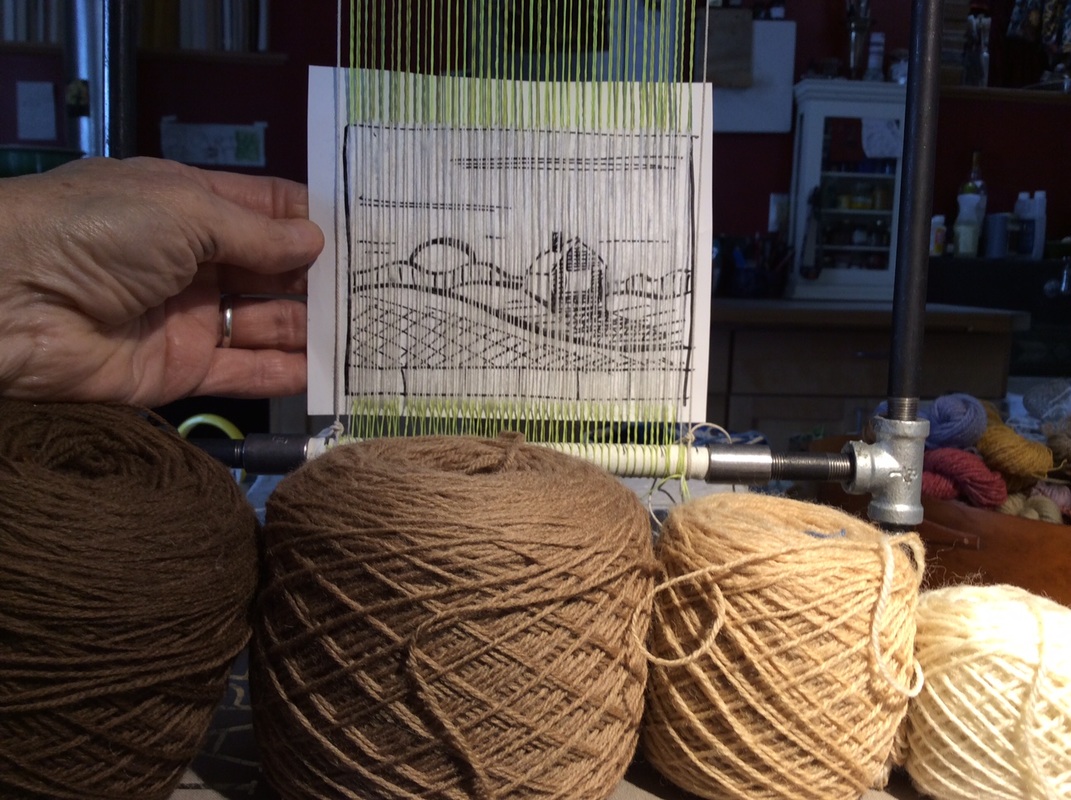

so though I have yarn that is darker brown and brighter white than I have chosen,

I don't want the intensity implied by such a broad value range.

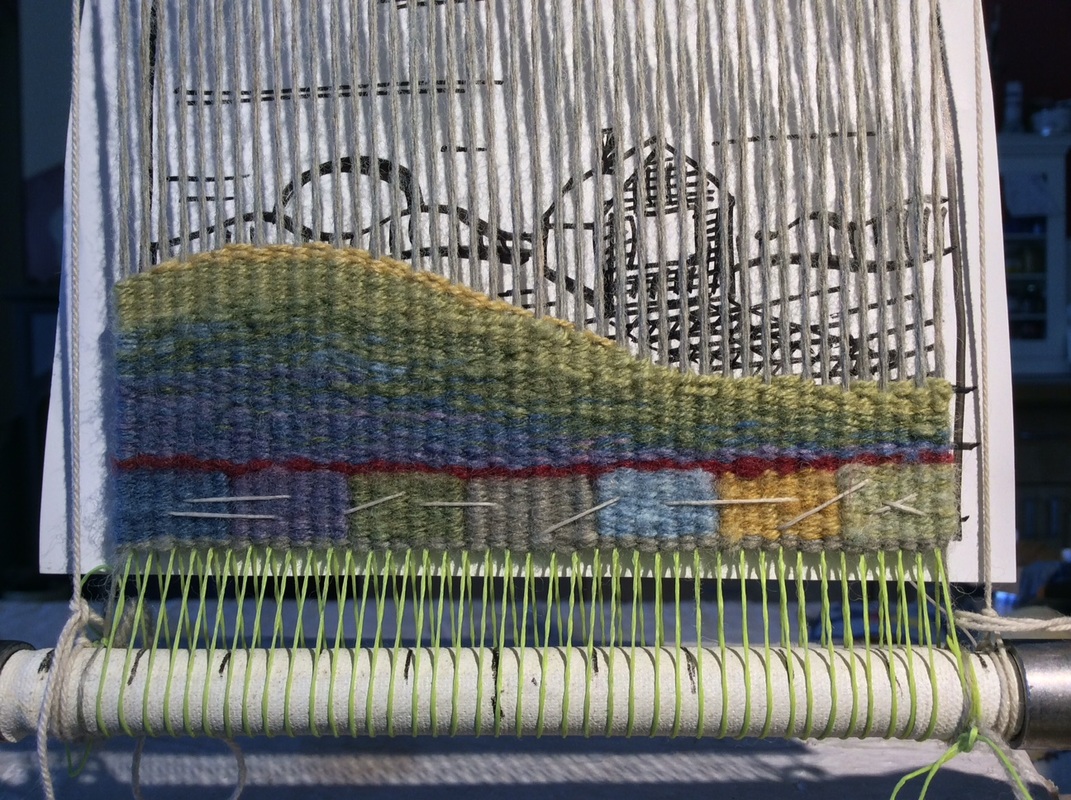

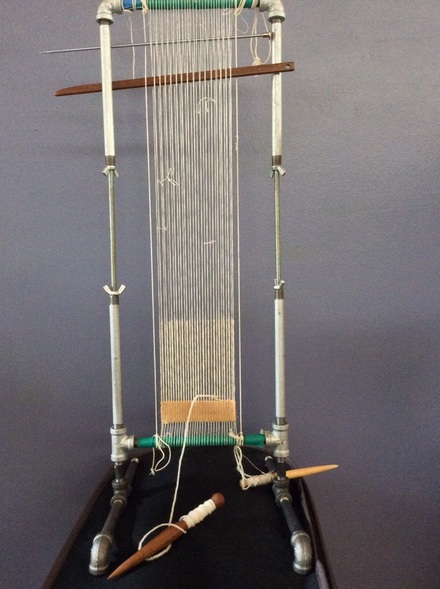

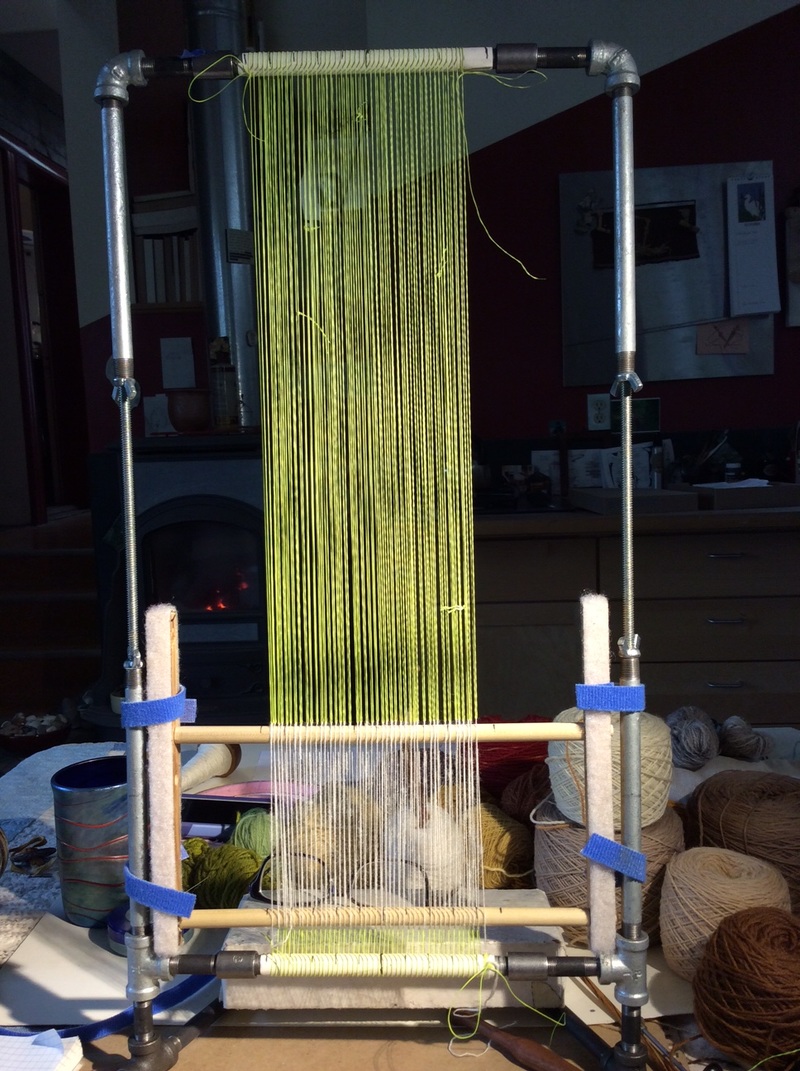

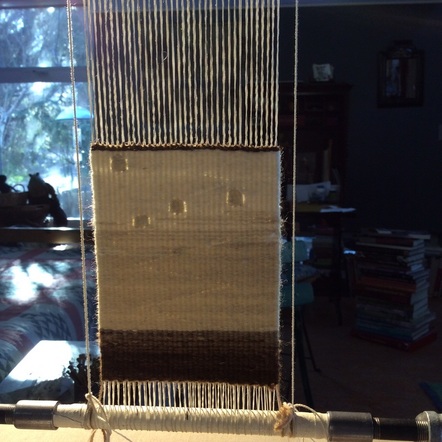

Also, the tapestry will be small, 3 1/2 " x 4 1/2" at a sett of 9 epi

and a limited palette of four balls of yarn is perfect for the scale of the cartoon

(cartoon is a name for the drawing used as a guide for weaving the tapestry)

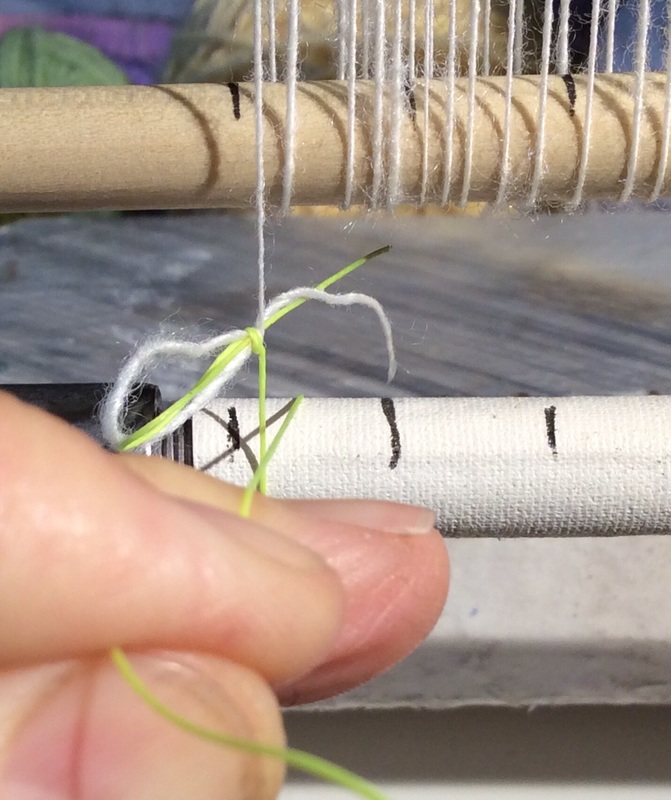

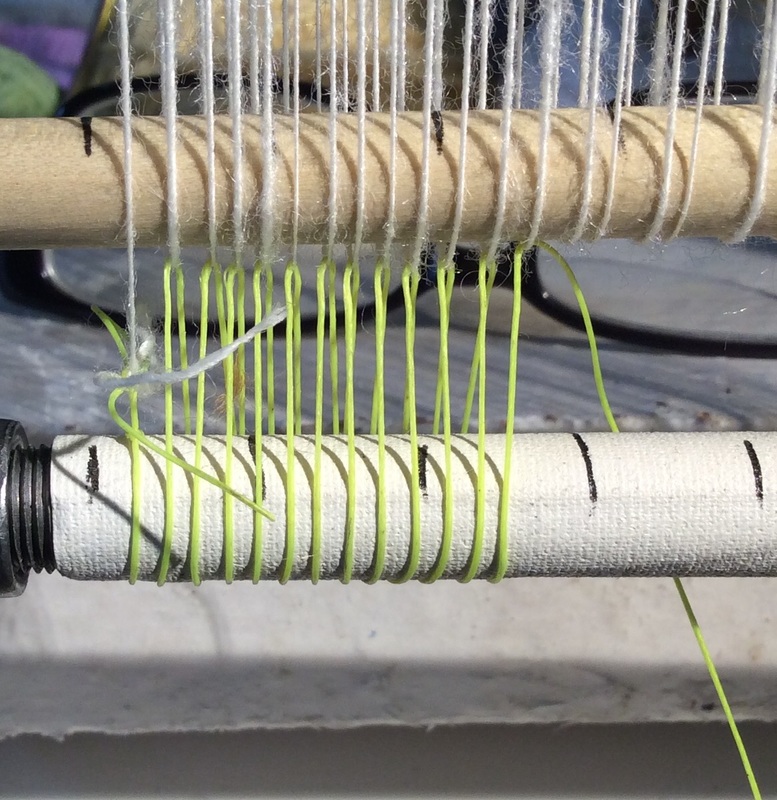

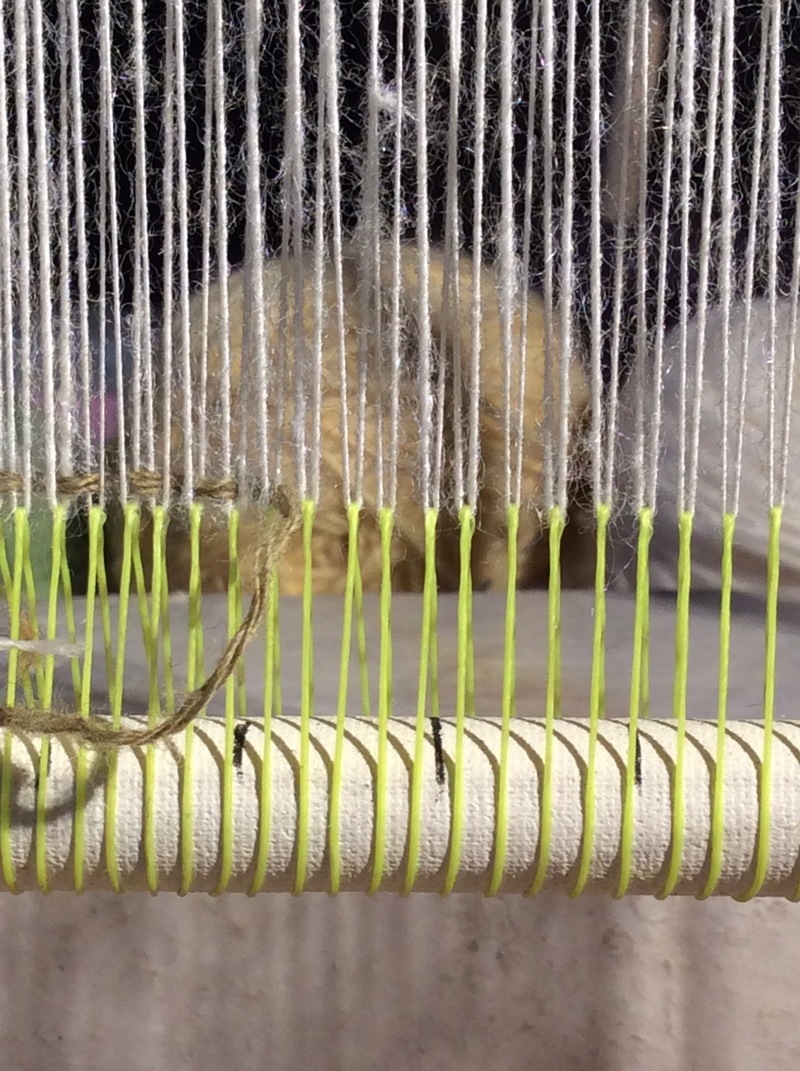

Additional middle values are easy to make by blending with multiple wefts

In this work, I decided to put the darkest value on the left

adding weight to the shadow at the bottom of the hill I am about to begin building.

And how light should the top of the hill become?

Also, I want to minimize the number of bobbins I have to deal with.

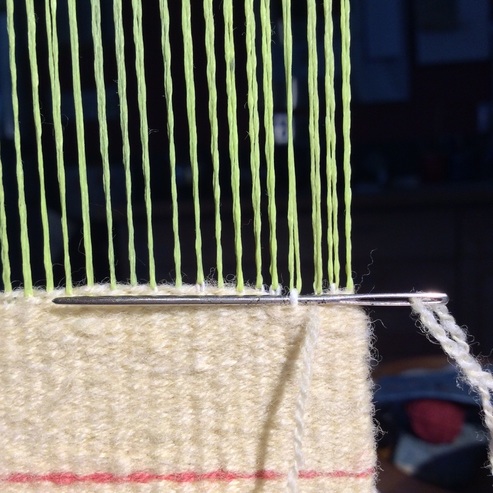

I hope to use no more than three values/blends across the shed, so starting with a blend means fewer bobbin changes. Irregular hatching allows me to build the shape while evenly progressing from the shadowed hollow of the hill to the curved top where the last light strikes.

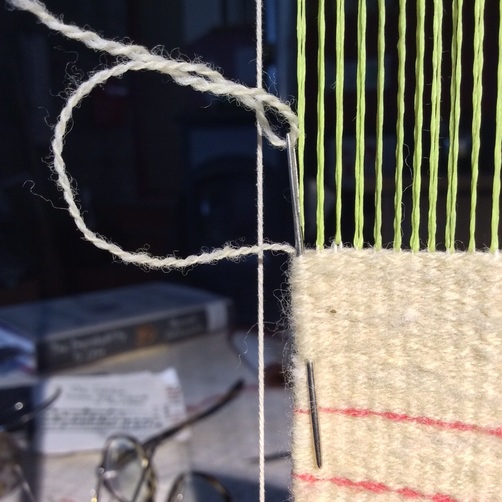

but added a line of eccentric weft -- a loosely draped final pass of light yarn--

all the way down the curved top of the hill to smooth and highlight it.

Eccentric weft is a useful technique for defining a curved shape but

it can distort the surface of a tapestry if there is not enough weft in the shed to 'stair step' down the woven shape. It also ceases to be effective if the angle or curve you are outlining is steeper than 45 degrees.

Value Question: Does the line of light yarn define the hill

or might an additional line of dark help to differentiate the first hill from the second?

Decision: A line of dark will be important as the tops of both hills have similar values.

Decision: If the entire shadow is the darkest value it will be heavy/stark. Better to weave most of it in the second darkest value then put in just a tiny bit of the pure dark brown at the base of the house to anchor it to the ground.

Value Question: I want the house to be a distinct shape but also belong in its environment.

Should the shadowed side be lighter or darker than the shadow it casts?

Decision: Make the house lighter than its shadow and give it a slightly different texture than the surrounding land by weaving it with a single strand of yarn.

Slits will also act as lines on the sides of the house

differentiating it from the surrounding hills.

Make the window the lightest of all and use a single strand of the lightest yarn

to connect it to what I think will be the value of the lightest part of the sky/ sun

Value Question: The roof--does it need an outline?

Decision: Yes. The outline defines the shape and implies a shadow, at least on the near side.

Value Questions: But how light should the roof be?

How dark the distant mountains?

nor as light as the brightest part of the sky behind it.

Its shape will be defined by the outline on the near and left sides.

The small slits on the left, between the roof and the sky

also make a subtle line. It does not need more.

Decision changed -- outline on the peak of the roof is too much. Remove.

Decision: The distant mountains could be a middle value to allow for distance and atmosphere, but for some reason I decided to use the second darkest color.

Can't remember why but it must have felt right at the time.

Uniform as in the cartoon, or should it grow darker as it moves toward the top?

How dark the clouds?

Decision: A few lines of cloud pull a hint of the darker value upward

Light at the bottom of the top cloud makes it seem bigger and closer

and also pulls a bit of light toward the top of the image, helping the eye to move around.

The sky should get slightly darker toward the top as skies do,

but not too dark or it will become heavy and shift the mood.

I know this because I made the top of the big cloud too dark when I first wove it.

I like it better now.

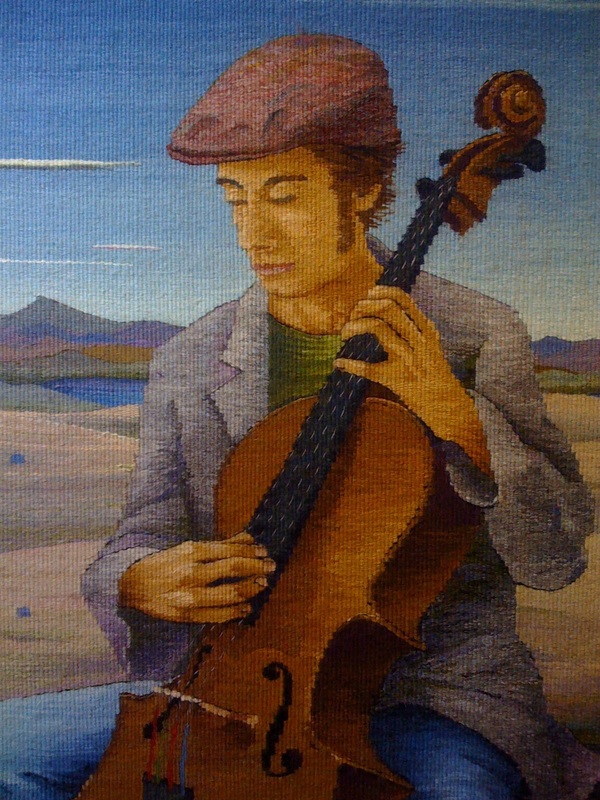

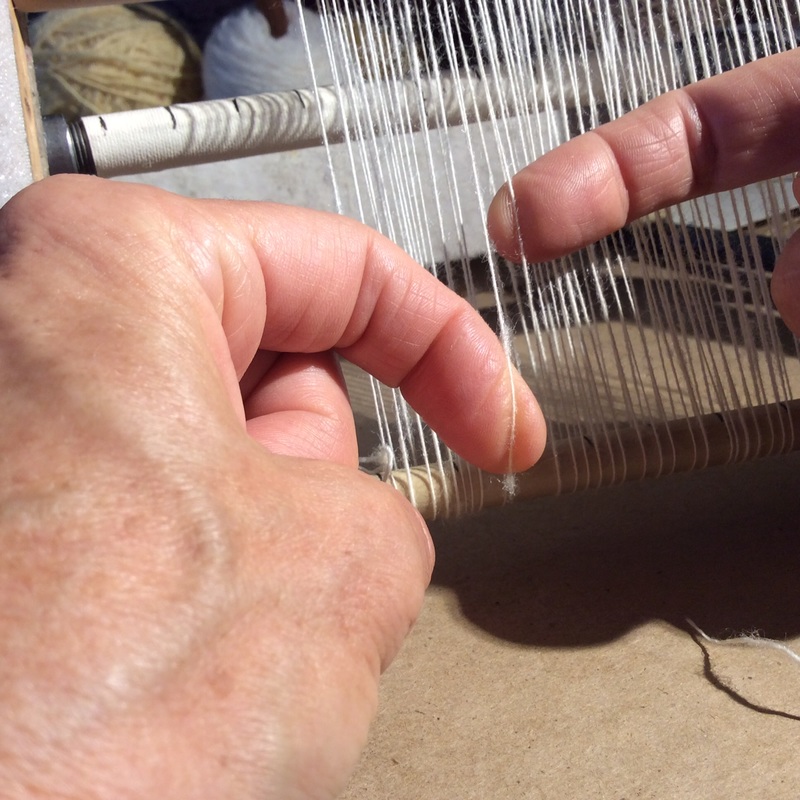

is like a long reciprocal conversation

between my hands and the yarn,

the yarn and my brain,

my brain and the image,

the image and my hands.

Round and round it goes with no right answers

but lots of interesting problems to solve --

small shifts of yarn,

micro dramas with every pass.

and sometimes a bit (or a lot) of unweaving.

You never know what is going to happen.

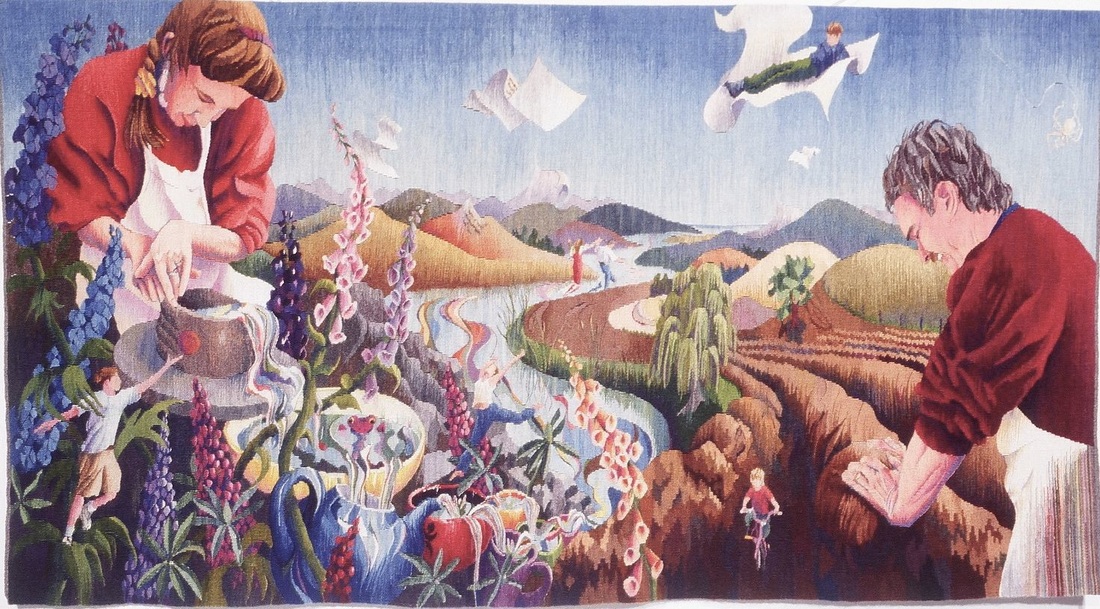

Yet I now live in one filled with color.

How this came to pass I cannot say, but I like to imagine a few adventurous golden souls crossing the prairie into a world of blue,

and cluster of green boats floating toward a region of red,

each hue sharing its skills and energy with the next.

What, I wonder, would it feel like to catch my first glimpse of violet if all I'd ever known was golden brown?

but however it unfolded, the colors among which I now live are hard to ignore.

Lively and thrilling like exuberant children, they demand to be part of everything

|

And why shouldn't they be?

We have dyes. And eyes. Why not use these myriad hues to replicate the colors of in the world and let value take care of itself? Why not, indeed. It is beyond the scope of this blog post to delve too far into color theory, for it is a lifelong study in itself, but value can't help but be part of the process, because colors have minds of their own and each hue, while consistent within its family, behaves entirely differently when hanging out with another. |

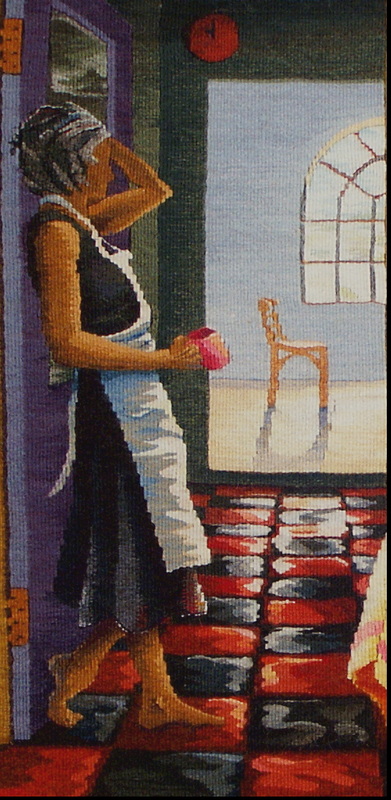

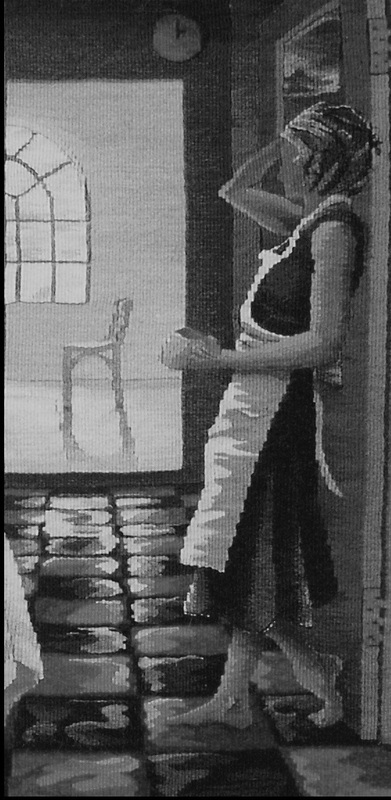

See what happens when the color is removed -- stripes gone!

But why does that matter?

After all, you can see the object for what it is in color so

who cares about the relative lightness or darkness of the hues?

Who hangs out in a black and white world anyway?

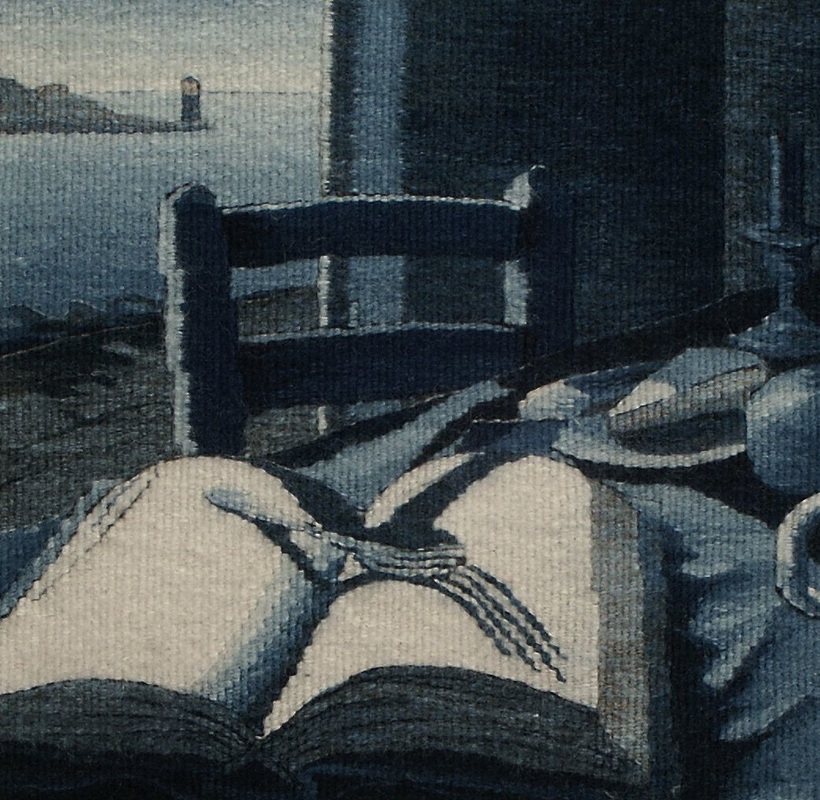

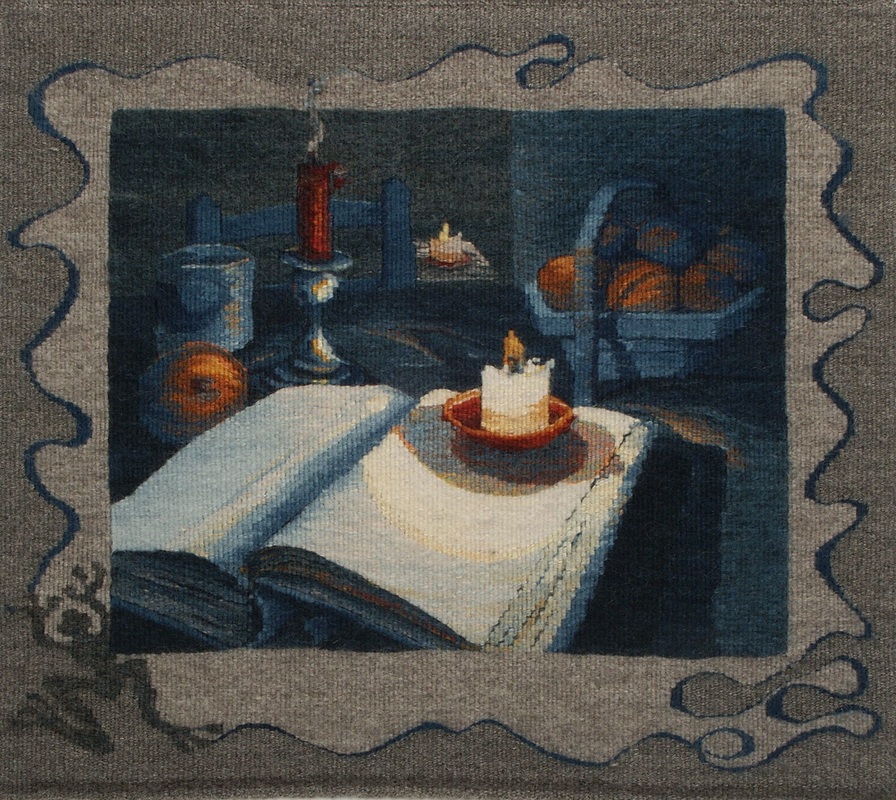

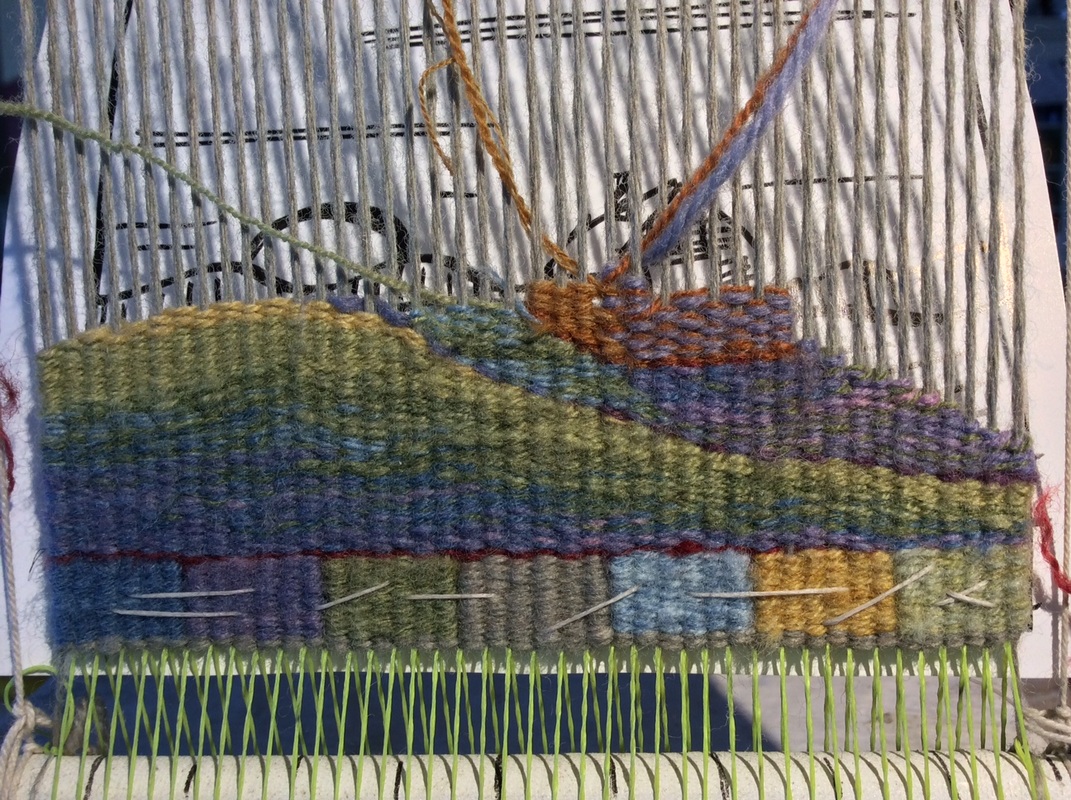

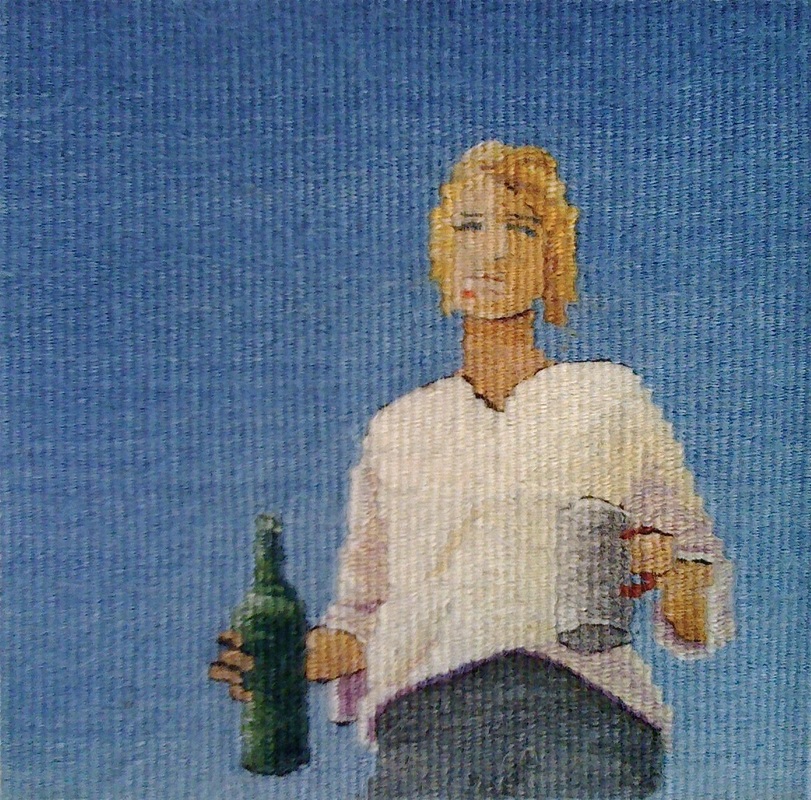

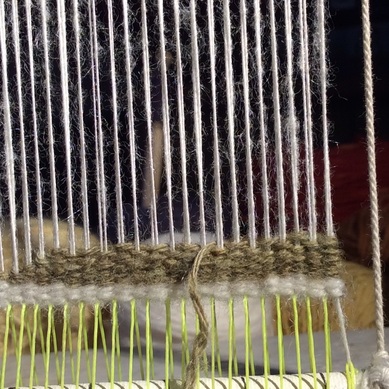

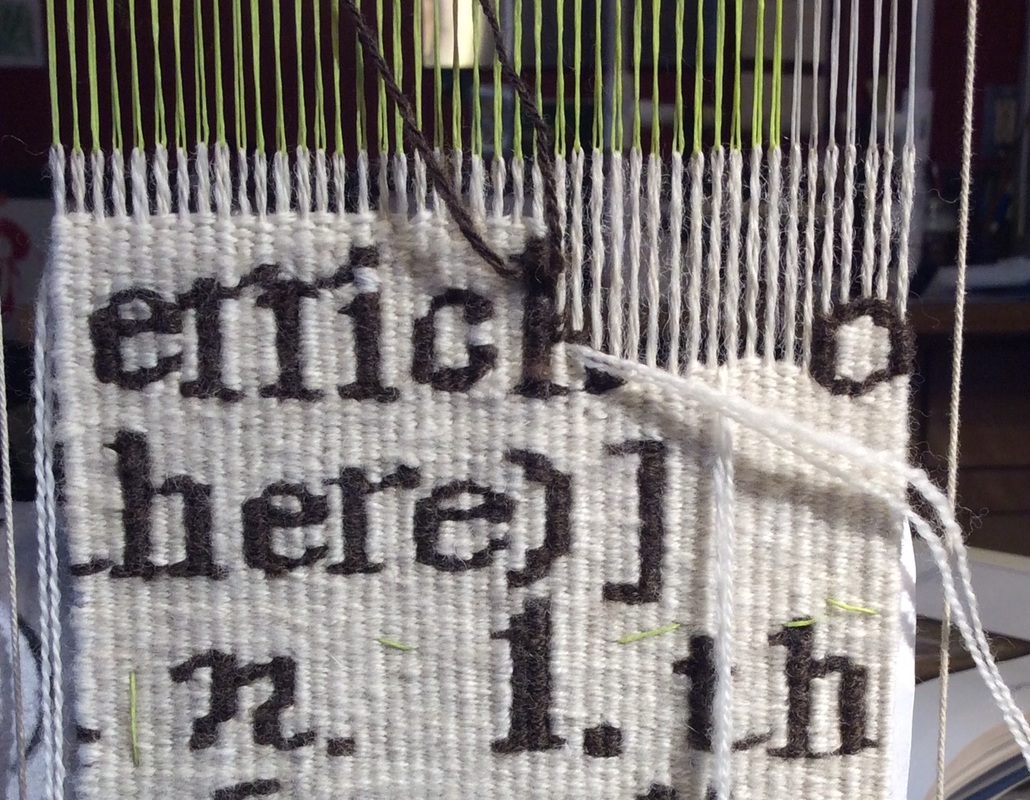

Rough Copy #2 - detail in progress

Rough Copy #2 - detail in progress

Well I do for one, whenever I can.

Indeed, the best way for me to create really satisfying colorful tapestries is to begin in that mono-hued world I described earlier and not think about the color until I am actually weaving.

I can then choose every strand of yarn based on value choices I have already made.

This simplifies the early stages

and makes time at the loom incredibly exciting.

|

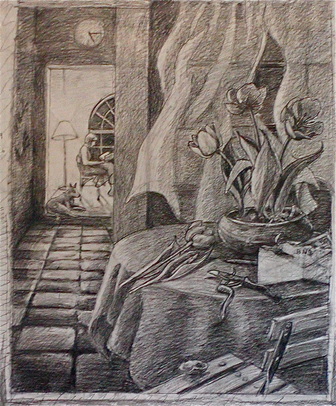

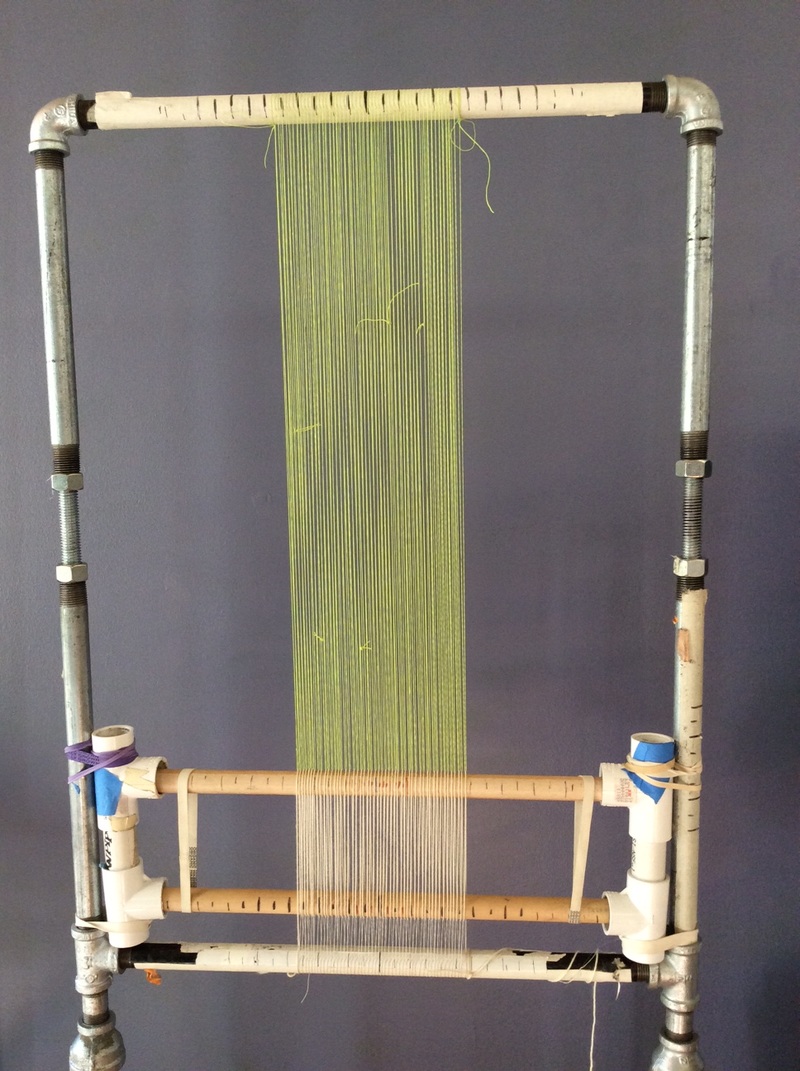

1. Make a Line Drawing with pencil on paper-- sometimes borrowing from my own photos but mostly just lifting simple shapes and ignoring detail. I want to be in charge of what I weave and not leave it to a camera that doesn't understand sett.

2. Scribble in the value and define form with pencils-- big soft ones are the most fun. 3. Erase. Draw. Erase. Draw Let image and mood evolve over time. One area might get lighter and lighter so even the darkest parts are lightish. Another, less of a focal point, might become muted so even the white things are grey. 4. Continue till I can't think of anything else to do. |

6. Choose one ball of yarn. All I need initially is something for the border. Everything else can and should build on that. Make subsequent choices based on what I have already woven.

Wool is not colored pencil, nor is it a marker, watercolor or light on a computer screen. It is a flexible column of air surrounded by many tiny fibers with untold facets and it, that thing we call a strand of yarn, will behave differently when woven than it does in the ball.

I cannot know how it will look until it is actually packed in.

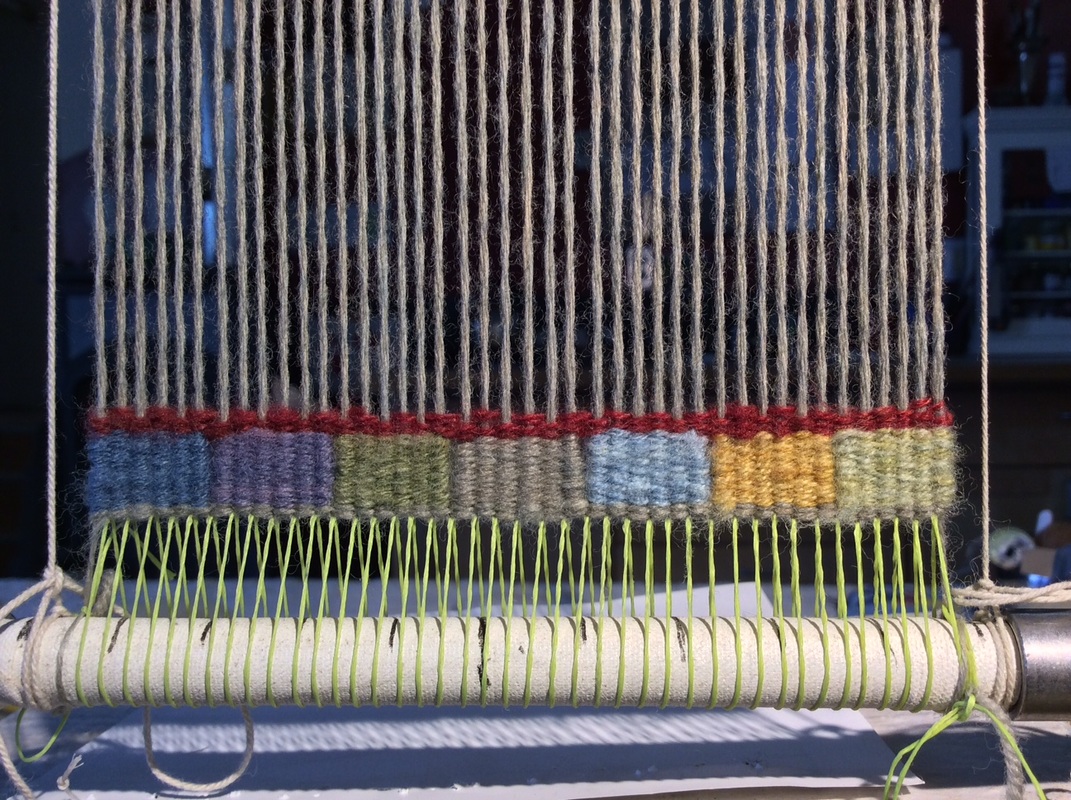

7. Arrange colors by area. When it is time to begin a certain part of the cartoon, I gather the value range for that thing in one basket: this group for the table cloth, this group for the floor, all the while comparing the relative value of that group with the cartoon and the other forms around it. Then I Continue to check the relative value of the yarn as I weave. Adding and subtracting as necessary.

Once upon a time I did this by squinting or looking at things in low light. These days, there are camera filters and apps that'll give you an idea of relative value in a second, though I still get to make the final decisions about everything. Cameras are not to be completely trusted.

Go for the glow.

Notice how all of the reds are darker but also brighter than the blues.

Plan to use them deliberately and sparingly.

8. Spin and/ or dye to fill out the range or shift my color/ value focus in response to how the tapestry is unfolding.

9. Remain alert for unexpected design/color/value thrills and pitfalls

like running or birdwatching or playing music.

The only way to do it is to do it--over and over until chords become your friends

and a kestrel is a kestrel even whizzing by in a car.

It is curious, actually, that most of us will play tunes again and again to get them right, but rarely reweave the same cartoon. Yet each time there is the potential to notice something new.

Having already made some decisions, and knowing from experience what works and what doesn't in, say, shape building, you are free to push color blending or value .

Or do it the other way--first focus on color blending and then on shape making.

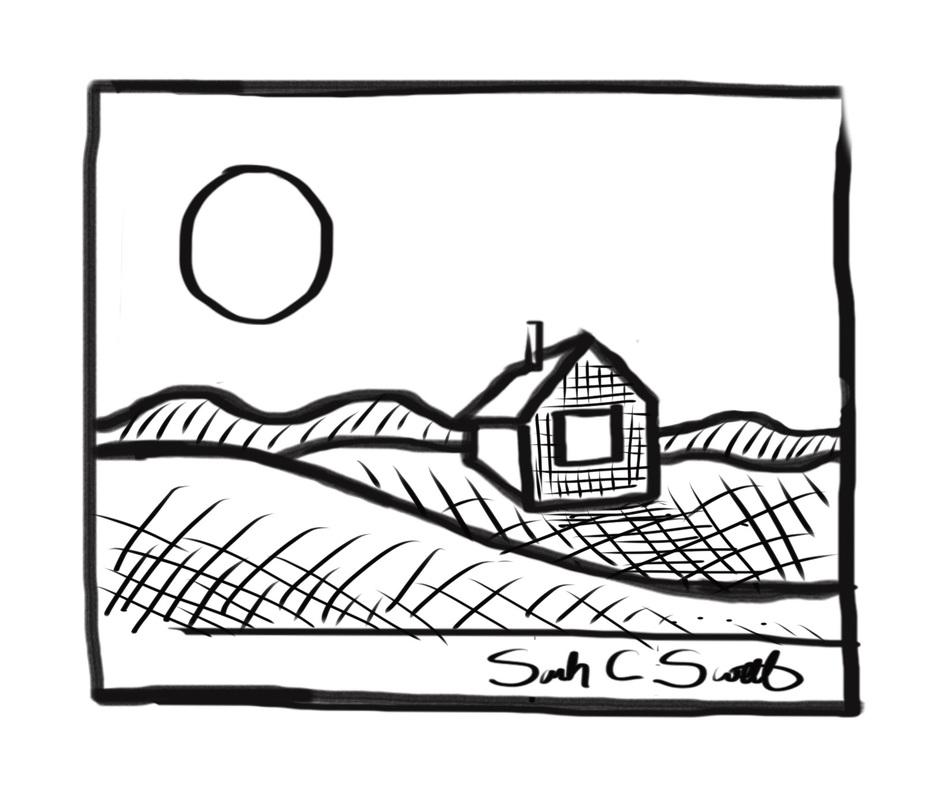

To help with this practice, if you're interested, here is a PDF of the cartoon for House on a Hill, the little brown tapestry I wove in detail up above. There are two versions -- with and without value hints, with and without a sun/ moon in the sky.

Click here, or on the image below to download it.

Print it out more than once if you like, and see happens with your hands and eye and yarn.

Below are some images of what I did (with less commentary than the brown one).

FYI: I was aiming for approximately the same value range as in the first.

As I wove this, I kept imagining other variations:

- If I turned the sun into a moon and made the the sky dark, what would the land do?

-If the darkest value were a creamy grey and the whole range very light, what would the landscape feel like?

- How dramatic could it be if the range of values went all the way from black to white?

so can you?

And if you do, can you show me how it turns out?

On Instagram use #tapestryunlimited and tag me (@sarahcswett)

On Ravelry join the Vancouver Yarn Ravelry Group-- #tapestryunlimited

Thank you for reading so far

and I wish you the best of good fortune with all the tapestries in your future.

Here are a couple of final thoughts..

1. Own you work--

and notice what you like

not what you think someone else will like,

or you think I might like,

but what actually stirs you.

Love value transitions but hate hatching? Learn to dye to make the intermediate values.

Love color blending and value transitions but hate dyeing? Try weaving with different materials to get the values you seek -- perhaps texture and shadow can play a part.

If you are a spinner, start with dyed fiber and blend with cards or combs.

Love value but are annoyed by color? Weave your own mono-hued world.

|

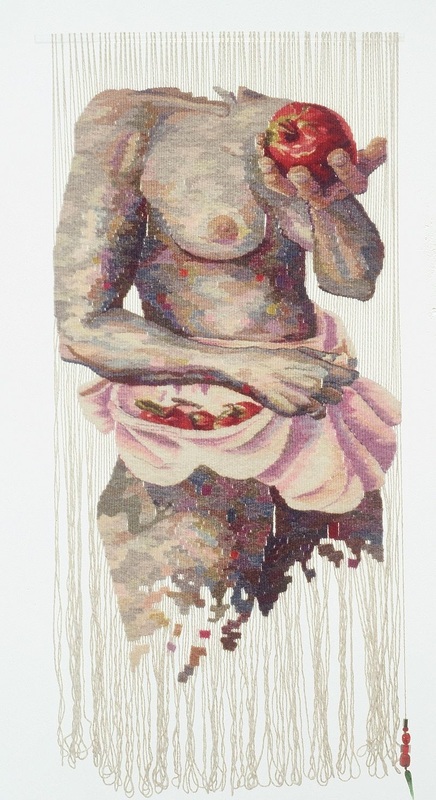

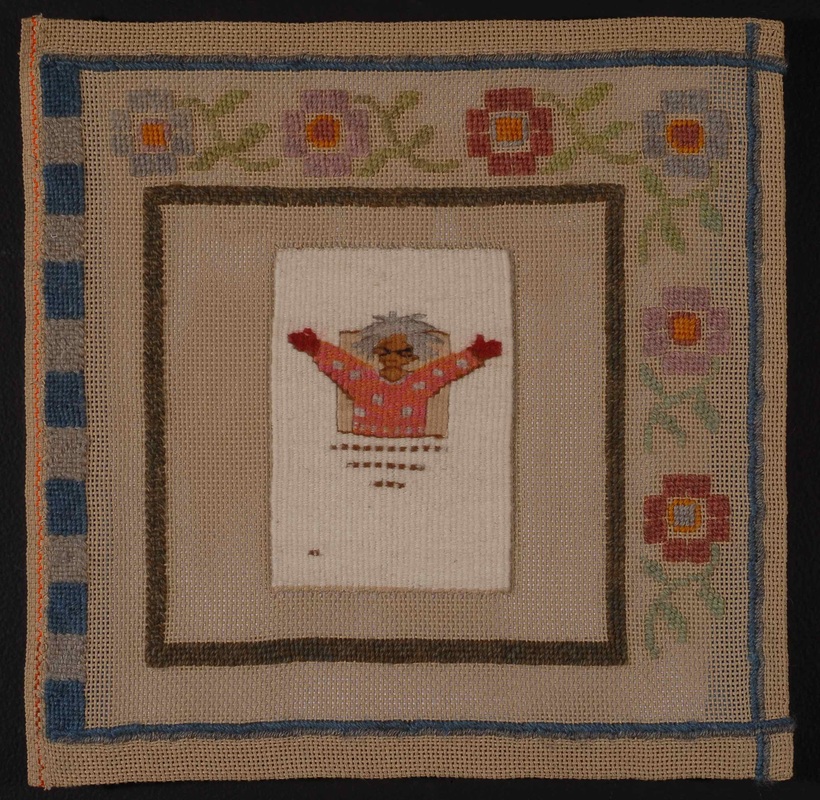

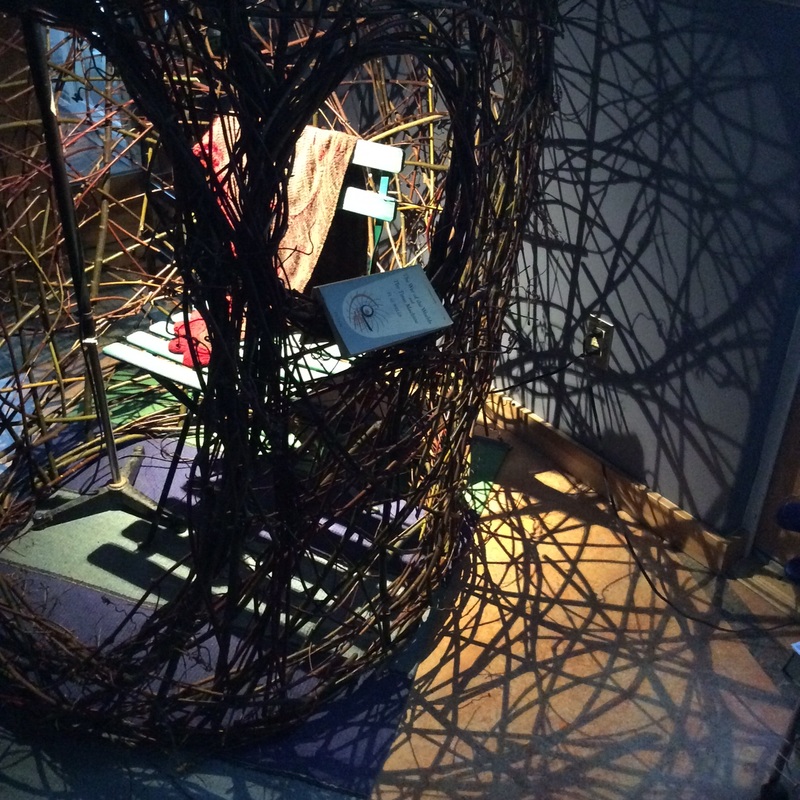

2. Relish the open space between art and craft where tapestry weavers dance in the sun, working with concepts that create art and practicing skills essential to the craft. Tapestry is a medium of endless potential, ancient and contemporary at once, and the structural limitations of warp and weft are a source of tremendous freedom. 3. So go forth and weave. The world needs your work. |

and its Tapestry Unlimited Exhibition,

an unjuried exhibition designed to showcase our best efforts at whatever level we find ourselves. There is more about both ATA and Tapestry Unlimited below,

but first, I want you to know that ATA is offering two prizes for participating in this blog tour:

The first is a one-year membership to the American Tapestry Alliance. The second is a one-year membership to ATA plus a free entry to the exhibition.

Current ATA members are not eligible to win, so there is lots of room.

I signed up for the exhibition today.

See you in the catalog!

---------

This blog tour is in celebration of ATA's annual unjuried exhibtion. Tapestry Unlimited; 11th International, Unjuried Small Format exhibition is open to all weavers. We are expecting upwards of 250 participants who will show their work at the Milwaukee Public Library this upcoming summer. Everyone who signs up to participate by January 31st 2016 will be included in the exhibition, and your tapestry does not need to be mailed to us until March 2016. There is an exhibition fee of $40 which pays for both the return postage for your tapestry as well an exhibition catalogue, which everyone’s tapestry will be featured in. We invite entries which work within more traditional definitions of tapestry as well as ones which expand upon them, including multimedia work.