I've written again and again

about the bliss of making

(and using)

coffee filter yarn.

NOTE: To explore these posts, click the coffee filter yarn, cellulosic experiments or tapestry buttons in the sidebar

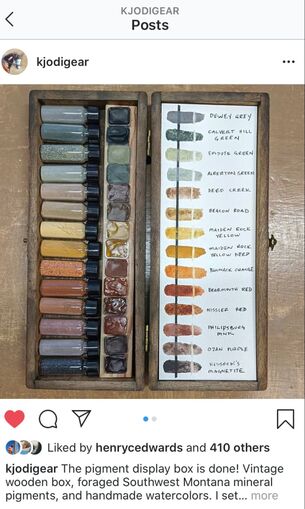

come from my friend Jodi,

the colors from her process

of turning plants and minerals

into pigments,

that she then transforms

into watercolors.

include links to her Instagram

and if you want to know more

about lake pigments (pictured above)

and mineral pigments (pictured below),

I highly recommend you click and scroll

for she has generously shared

a great deal of information on her feed.

for all the photos of cutting,

adding twist,

and weaving

what I have not talked about

is how the colors

stick to the filters

in the first place.

And the reason for this

is that they don't.

which chemically bond with a fiber or a mordant,

or watercolors (and other paints),

where the finished pigment is mixed with a binder,

the particles of color on the filters

are essentially resting in place,

a bit like stains,

and are thus both fragile and potentially fugitive.

At first I didn't care about this--

didn't, in fact, even think about it.

I just wanted to learn and play.

They were just coffee filters for goodness sake,

fished from Jodi's garbage can.

But as I spun more of them,

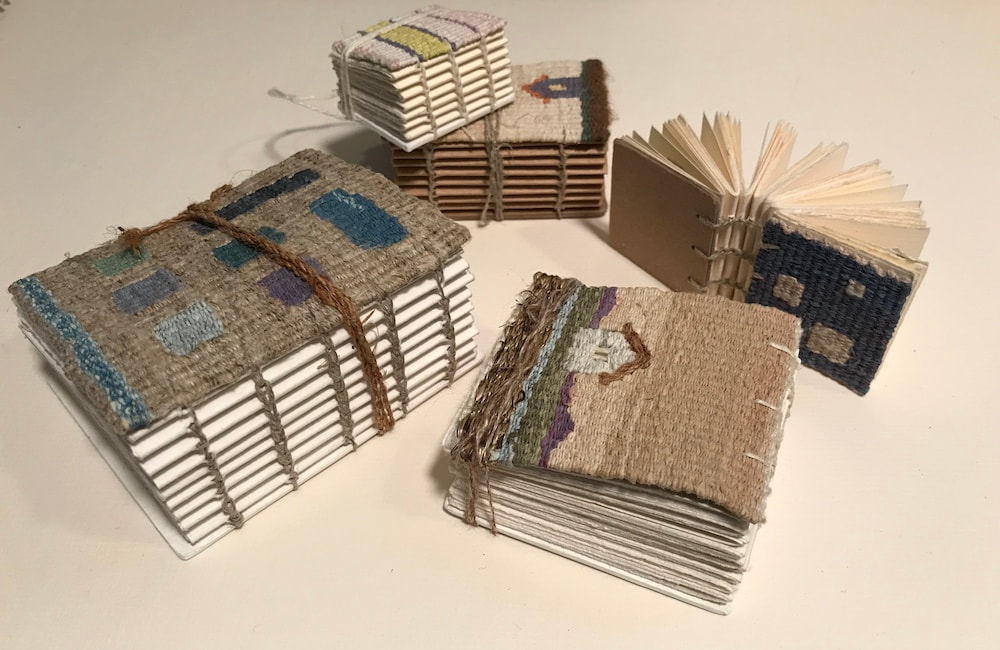

wove paper tapestries,

and made the tapestries into books,

I couldn't help but notice

the occasional bit of color

coming off on my hands.

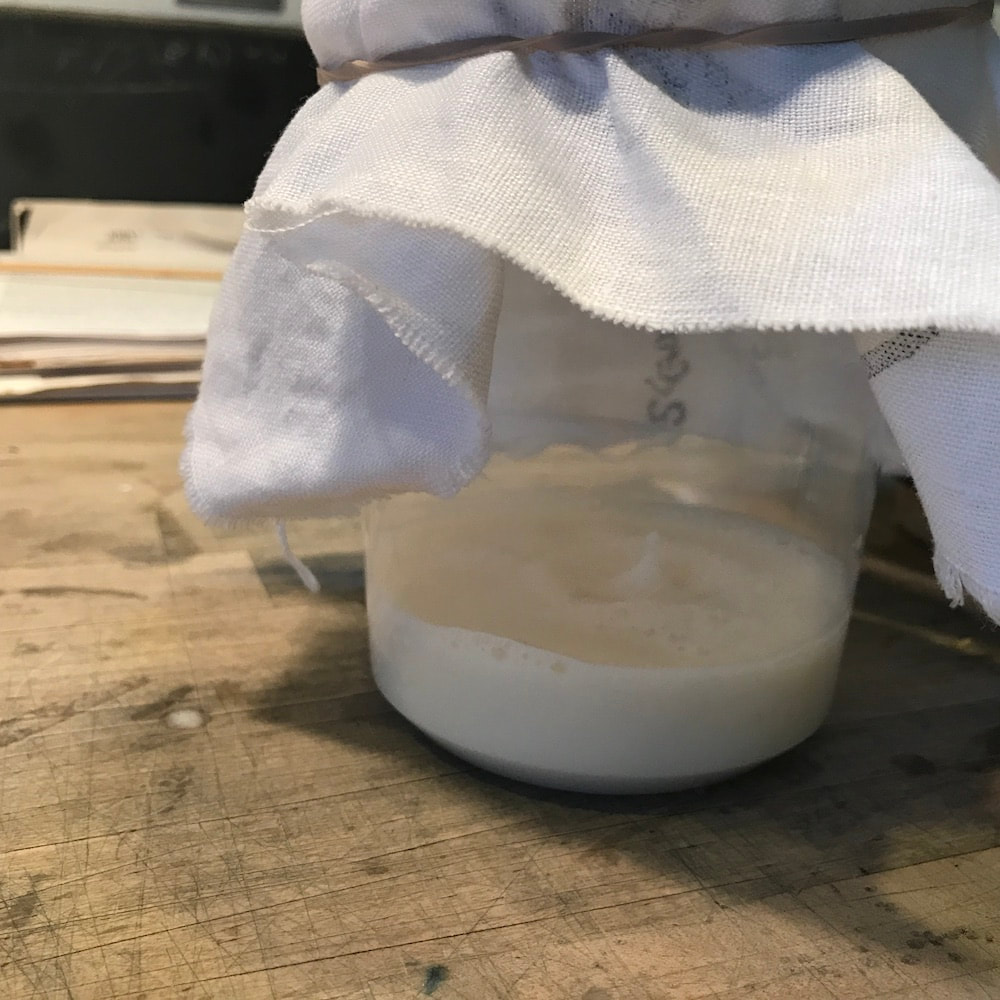

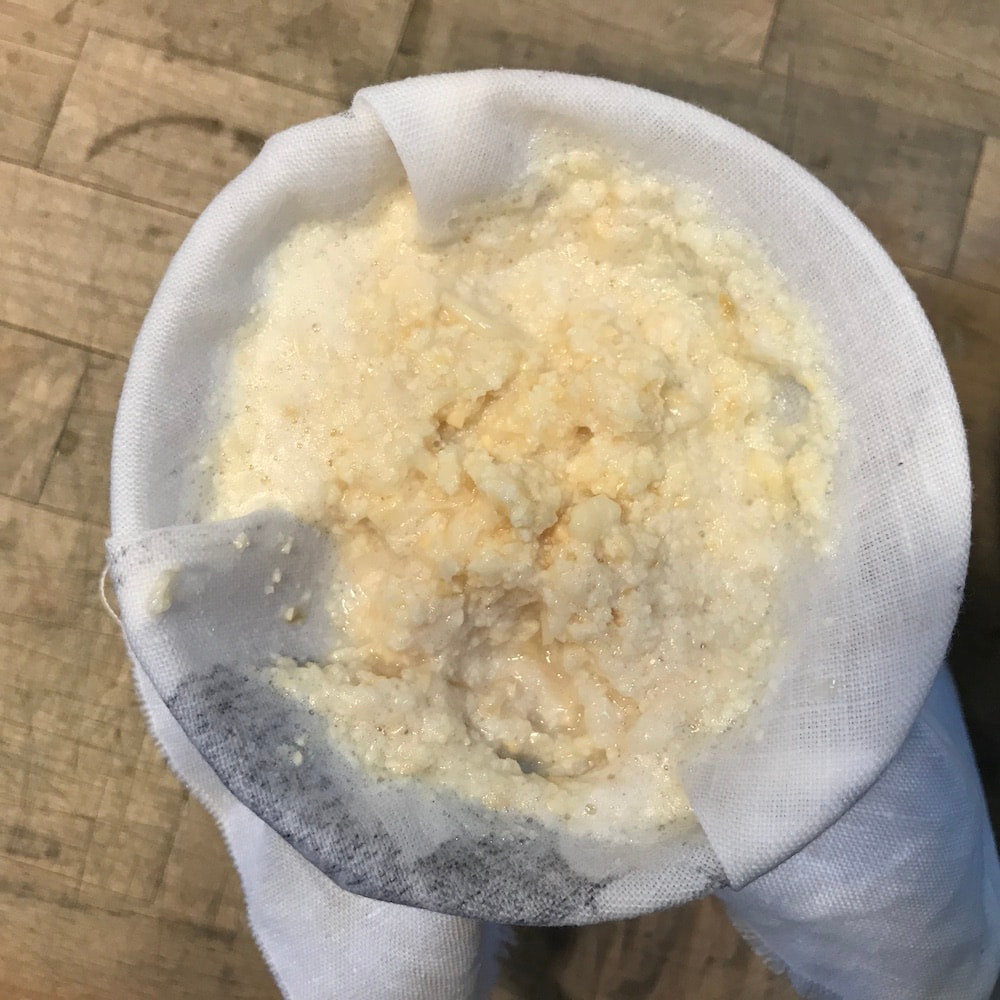

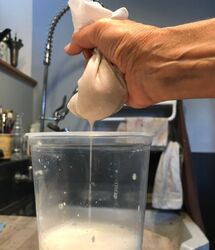

Soy Milk.

the stuff from the grocery store,

but rather the white milky liquid

you get when

a handful of soybeans,

has been

soaked,

rinsed,

crushed,

thoroughly masticated with water,

(faster with a blender than a suribachi

if not as photogenic),

then filtered

and

diluted.

it works like this:

when applied to fibers,

the proteins in the soy

(long chain polymers),

literally grab both the pigment particles

and the particles of paper

(or fiber if that is what you are using),

and hold on

in a kind of ever-tightening group hug

that won't let go,

the bond growing stronger over time

as the soy cures.

The process is called polymerization.

(explanation seriously oversimplified, of course).

around the world and across the web,

but since I learned about it

many years ago

from the amazing John Marshall

I will send you straight to

-his recipe for making soy milk,

-his book, Salvation Through Soy,

and hope that while you are there

you check out more of his website

for his work in all areas

(katazome, fresh indigo dyeing, historic Japanese textiles....)

is fascinating and comprehensive.

He is also a generous and lovely person

and puts on a damned fine workshop.

one of the ways that John uses soy milk

is as a "post sizing"--

a kind of fabric finish

that protects the cloth as well as binding the pigment

and that is the way I have been using it--

as though the filters were finished cloth.

Ideally,

I would have dipped

all of the colored filters in soy milk

the moment they arrived from Jodi

so they could have been curing

during the months I was working on other things.

Buy since I did not think about it then,

I've now been using it in three ways:

1. dipping the remaining uncut filters and letting them dry

2. winding the paper yarn onto my willow distaffs,

painting the strands (as in the photo above),

then re-winding onto paper purns when dry.

3. painting the soy milk onto finished tapestries.

And that is where I am now.

has been curing for about a month,

and though it is probably a little early,

I may soon cut and spin a few

and try some rub tests,

just to see.

to treat the finished tapestries with soy milk--

not only to keep the pigments in place

but also for the long term protection

(what John has called the 'natural scotch-guard' effect),

provided the cured polymer--

especially those tapestries that will go on

to have a working life.

and in the meantime,

feel free to use the comments

to share your own information

and experiences

with all of us.

Thanks!

Now, back to it.